Review of Know the MOther

By Natalie Rowland

"Why do we wake each night in that spiritless moment between worlds, we mothers and daughters and wives? And why does the night abandon us to twinkling worry, to the rattling breaths of our children, to the hard floor of our long prayers?"

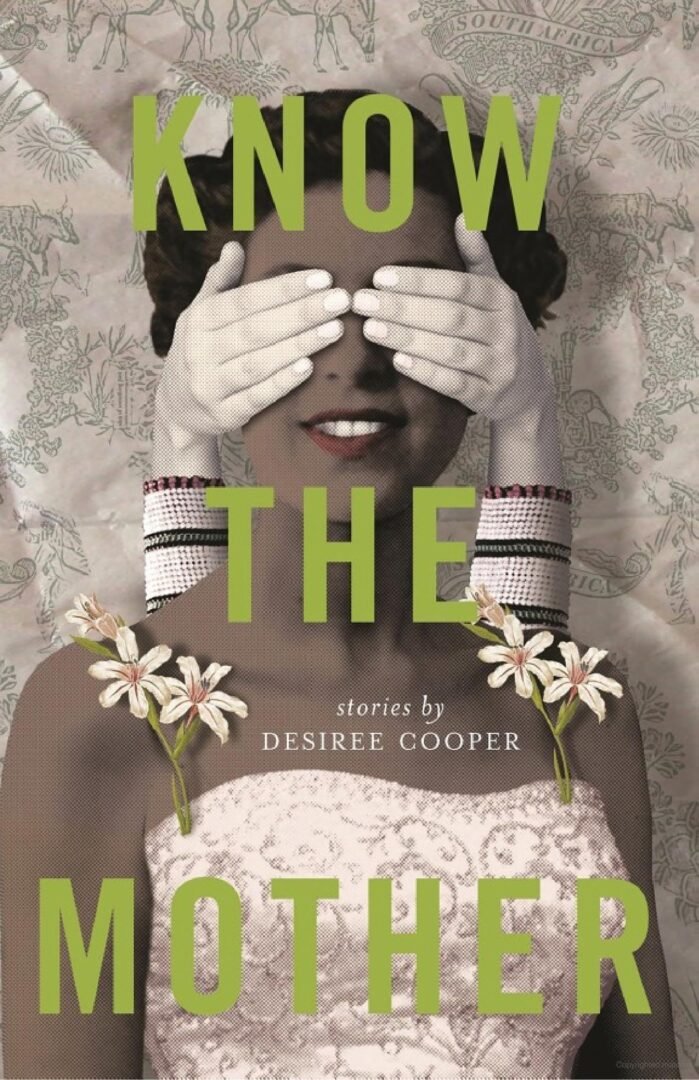

So enchants "Witching Hour," the opener in Desiree Cooper's ghostly Know the Mother. I came to the book late to publication (2016) but on time in the disorienting haze of my own motherhood. While this was Cooper's first fiction collection, she was no stranger to successful writing: a Pulitzer-nominated journalist and founding member of Cave Canem, a home for Black poetry. The pieces in Know capture the everyday, some a few paragraphs, the average around two pages. They're readable in gulps, between the complaints of a two-year-old and the cry of a newborn, or "in that spiritless moment between worlds" The book fits alongside Rivka Galchen's Little Labors; the breadth of Cooper's protagonists fans out nicely next to Galchen's first-person observations.

Know is not so much for mothers as it is about them, so there are bound to be resonant moments for the reader who has or has had a mother (i.e. anyone). Cooper plumbs motherhood through others: a child reads his parents' body language and realizes he's inadvertently chosen sides ("One Candle Left"), a father and daughter skirt emotional connection in "Feeding the Lions," and a spouse rages in "Away from the Woodsman." In the title story, a daughter washes her elderly mom's back: "Already, she smells like a garden unearthed, a freshly dug grave." One husband claims, "She wasn't a mother"she was a producer. Even when they were home alone, everything was a little too bright, a little too worthy of an audience."

Mothers' perspectives are written well, too, with the anxiety, resentment, guilt, love, and exhaustion that shadow them. Mothers are thrust into traumatic racism: "Reporting for Duty, 1959," "In the Ginza," "Home for the Holidays," and "The Disappearing Girl." A corporate woman miscarries at work in "Cartoon Blue." A husband mocks his wife for mothering him ("Home for the Holidays"). A sick mother yearns to be mothered in "Leftovers" even as she exults, "My nudity is neither sexy nor fecund. Finally, I am neither a lover's plaything or a child's milk bar." Cooper reimagines mothers from one story to the next, and she writes with tenderness (a skill that shines in "The Massage"). A few stories made a jarring launch from her usual realism to dream-state surrealism ("Soft Landing," "Second Sleep"), and "Something Falls in the Night" is effective in this way as a mother rehearses escape plans in response to a burglary.

If the book's innards collectively depict A Mother, she is fragmented, shape-shifting, economically diverse, multi-racial. Her life is ranging, and Cooper paints her portrait episodically. The Mother is resented, venerable, dead, present, judged, beloved. Cooper's chief success is in excavating a deceptively simple noun, assembling glances at a subject so composite she can only be known through stories.

Natalie Rowland earned her MFA from Florida Atlantic University, where she served as the founding managing editor of Swamp Ape Review, and her BA in comparative literature from the University of Michigan. Her work has appeared in Booth, Hobart, The Rumpus, and Fiction Writers Review. She currently lives and writes in Grand Rapids, Michigan.